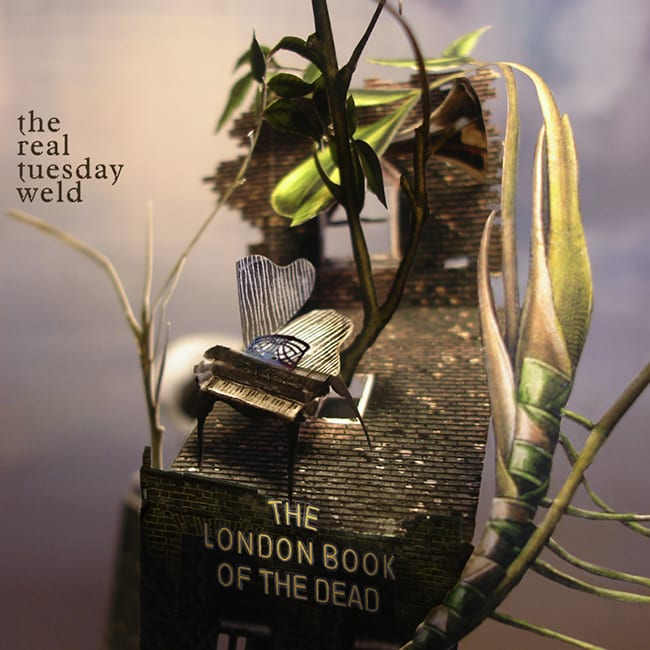

The Real Tuesday Weld

The first thing that strikes you about any album by Stephen Coates (a.k.a. The Real Tuesday Weld) is the fact that every element in his compositions seems to be drawn from sources many decades old. The second thing that strikes you is that his music sounds completely new.

The first thing that strikes you about any album by Stephen Coates (a.k.a. The Real Tuesday Weld) is the fact that every element in his compositions seems to be drawn from sources many decades old. The second thing that strikes you is that his music sounds completely new.

For Coates, the breakthrough in his professional journey came in the form of a pair of surreal dreams in which he was visited by the legendary English music hall singer Al Bowlly and the late actress Tuesday Weld. These experiences convinced him to focus on a career in music and eventually led to the recording of an EP (The Valentine EP), which would be followed shortly by the full-length When Cupid Meets Psyche. His sophomore album and debut on Six Degrees is a deeply complex and lovely full-length CD titled I, Lucifer. The album is a conceived soundtrack to Glen Duncan’s (Coates’ friend and former flat mate) book of the same name about the Devil’s take on humanity. Coates’s follow-up release on Six Degrees, The Return of the Clerkenwell Kid, continued to develop what Coates has come to call his “antique beat” sound, putting modern technology to the task of creating new music out of a kaleidoscopic array of old sound sources. The sound of The Return of the Clerkenwell Kid was somewhat different from that of its predecessor, but the modus operandi remained basically the same and no one would ever mistake it for anything other than a Real Tuesday Weld album.

Which brings us to his latest, and anxiously awaited, album for the Six Degrees label. The London Book of the Dead may sound at first like a startlingly morose title, but in fact it’s more whimsically humorous than morbid. It refers to the Bardo Thodol (or Tibetan Book of the Dead), which describes the passage of the soul from the end of one life to the beginning of another. “I thought it would be funny if there were a book like that for the English,” says Coates. “The album felt like that to me – a way of moving from one state to another, and all set against the backdrop of this city.”

Amongst the whimsy and humor are lyrical concerns drifting between such weighty topics as death, religious faith, honesty, drugs, and disease. The songs are informed in part by Coates’s own recent passage through several significant events: “Last year I became a father, and then two weeks later my own father died,” he says. “So I was in this kind of psychic spin between birth and death, and this album came out of that in some way.”

But even when the going gets dark and introspective, there’s an element of musical whimsy that is never far from the surface. Consider, for example, “Kix” – a gently humorous expression of romantic realism (“I don’t get my kicks out of you/I don’t feel the way I used to”) in which he praises the object of his affection for her qualities but acknowledges that drugs and drink now offer him more of a charge than she does. It’s ultimately a rather bitter song, but it’s also an explicitly funny sendup of the Cole Porter standard “I Get a Kick Out of You,” an American Songbook classic that expresses just the opposite sentiment. Coates juxtaposes his lyrical inversion of Porter’s original with a similarly inverted musical accompaniment – one that takes swinging clarinet and gypsy-jazz violin and pairs them with the kind of gently thumping beat (and subtly elegant turntable flourishes).

In fact, sly juxtaposition is the rule everywhere on this fascinating album: “The Decline and Fall of the Clerkenwell Kid” starts out with bluegrass banjo, which then segues into a section featuring a melancholy clarinet; the two are later joined and combined with a fragmentary spoken word section. On “It’s a Wonderful Li(f)e,” a jazzy instrumental setting is provided for the decidedly dour lines “You say it’s a wonderful life” and “You know that’s a wonderful lie.” On “I Believe,” Coates takes a leaf from U2’s lyric book and offers a litany of things in which he believes – but typically, the list is complicated and at times self-contradictory (it includes monogamy, lust, technique, sarcomas, and opiates). The last item on each list is “love,” of course, but he manages to give even that obvious entry a twist that may or may not be ironic: “I believe in people who I believe believe in love.”

The album’s emotional center is actually located at the end of the program: “Bringing the Body Back Home,” despite its generally gloomy tone, it’s a sweet and ultimately encouraging waltz that arrives at a philosophical conclusion: “Love is the one thing worth living for.” If that line came at the end of a less thoughtful and complicated album (or maybe even at the beginning of this one) it would come across as merely banal. But as a coda to The London Book of the Dead, it feels like the hard-won conclusion to a long and difficult thought process – one that, despite its difficulty, has yielded tremendous and straightforward musical pleasure to those who witnessed it.

The Real Tuesday Weld’s music has fascinated more than just listeners and critics – it has also drawn the attention of major advertisers, and has been licensed to accompany ads for Cherry Coke (you may have seen the commercial in which cherries fall from the sky onto a bewildered but eventually delighted urban crowd, while Coates’s “I Love the Rain” plays in the background) and for TV shows like Weeds (Showtime), Gilmore Girls (WB) and Nip/Tuck (FX). All of this speaks to not only to Coates’s finely wrought sense of irony, but also to his “anything goes” musical approach: asked about his often unusual instrumental choices, he responds, “banjo, kazoo, potato peeler, you name it – I’ll stick anything in.”

The London Book of the Dead is just one more example of how a wildly open attitude and a slightly mystical bent can result in a distinctly personal and wonderfully warm musical personality – one that uses technology enthusiastically and happily turns it against itself to create something that sounds more deeply human than most of the music made by analog means elsewhere.